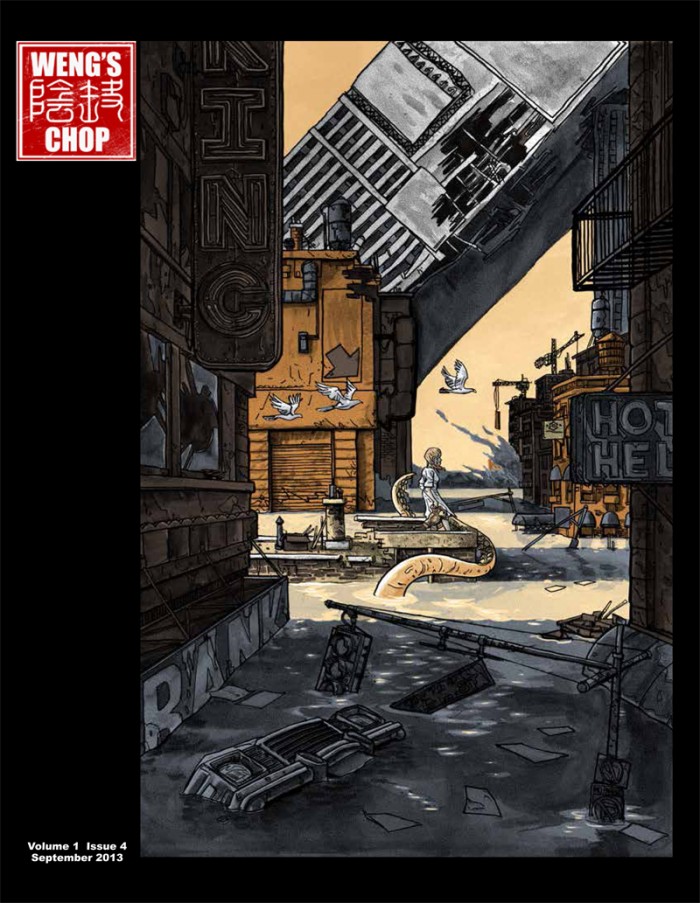

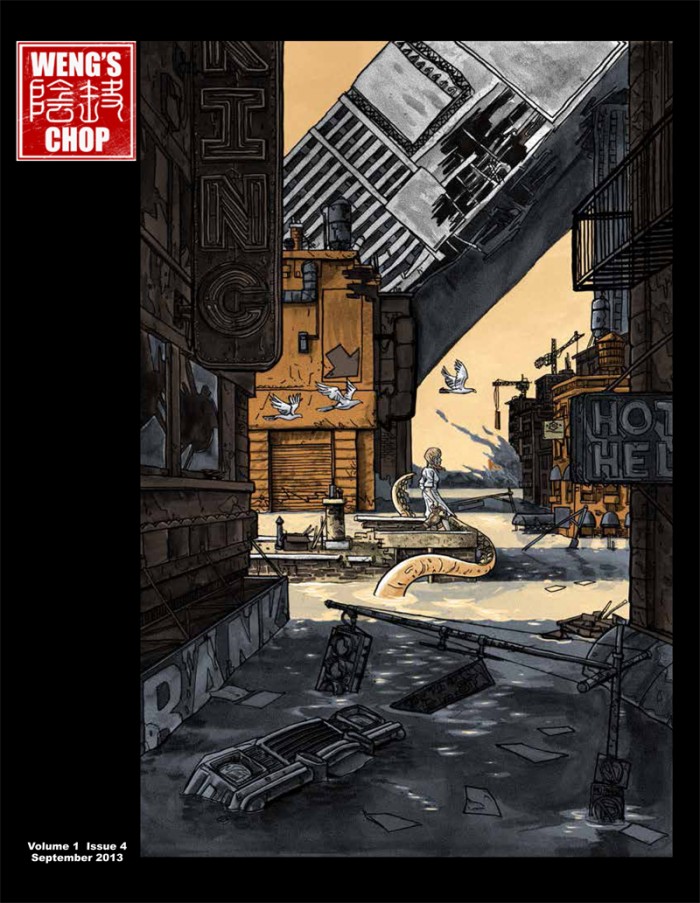

Below is a GIANT interview I did for the amazing genre magazine, WENG’S CHOP a few months back, conducted by the VERY PATIENT Tony Strauss. They were very kind and allowed me to reproduce it here! If you’d like to order a copy of the magazine, which features a LOT more content than just this, please go to one of these links below! (interview follows)

Chances are, if you’re into cool poster art, you’re familiar with Tim Doyle. Over the past few years, his work has graced many a one-sheet of the revival screenings of some of your favorite movies, and it’s likely he’s done a gig poster for one of your favorite bands. When you’re doing some of your geekiest online image browsing, searching for awesome images inspired by your favorite nerdy obsession, you’ve seen his art. If you’re a collector of limited edition posters, you probably own—or have at least bid on—some of his work. Tim Doyle is everywhere…in fact, he’s behind you RIGHT NOW!

READ THE REST OF THE INTERVIEW AFTER THE JUMP BELOW!

Mr. Doyle recently took time out of his are-you-fucking-kidding-me busy schedule to submit to a proper interrogation, WENG’S CHOP-style. Cleverly assuming the persona of a one-man Good Cop/Bad Cop with no pants and an unidentifiable tropical rash*, I quickly broke the poor lad’s spirit, and he gave up the goods. Seriously…he spilled the beans on EVERYTHING—his Secret Origin, lackademia, the deceptive glamour of comics, the back hallway of the Alamo Drafthouse, defibrillating Mondo, proper video store management tactics, the secrets behind The Rise of the Mighty Nakatomi, starving artists, and world domination. Hopefully, with a few years of physical and psychological therapy, he’ll recover nicely, and realize that it was all in the name of WENG’S CHOP getting what it wants—and therefore, totally worth the traumas he experienced.

* Officer Kahuna McRash’s Interrogation Techniques® instruction guides are available at your local library.

Interview conducted by Tony Strauss

Thank you for taking the time to chat, Tim! I’d like to start off by asking you about your Humble Beginnings, before you evolved into the Graphic Superstar that you are today. You’re originally from the Dallas part of the world, correct? Did you have any formal art training there in your youthful days, or are you more of the self-taught variety of artist?

Thank you for doing this interview! I’d hardly call myself a “Graphic Superstar”, but I’ll take the compliment. I prefer “guy who pays his bills by drawing silly stuff,” which I guess is pretty rare, all things considered.

I was born in Claymont, Delaware back in ‘77, but we moved to Plano, Texas in ‘79. Back then it was a smallish suburb of Dallas, and now the damn place is a giant, weird, town—full of shopping malls and aimless teenagers with more money than sense. Instead of getting into sports, or cars, or sports-cars, or black-tar heroin like the other kids I grew up with, I fell hard into comic books and cartoons—not too weird now, but this was the ‘80s—back when you could get called “faggot” for wearing a Batman t-shirt…you know—back when it was actually hard to be a nerd. And while I’m at it—YOU KIDS GET OFF MY LAWN! Christ, I’m getting grouchy in my mid-30s. (I’m holding hard to the “mid” part of that sentence, there.)

My parents, while I wouldn’t describe them as “artsy”, I would describe as very supportive of my brother and I, and of our artistic or musical pursuits. My mother spent a lot of time drawing with me as a child, and between that and the comic books, drawing just became a thing I couldn’t stop doing. Somewhere in there, my dad bought me a copy of How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, and then it was all over from that point.

I took Choir in middle school for some damn reason, and switched to Art in high school. As an aside, the Choir kids I had been friends with for three years were really weird with me for “dropping out”. One of the guys actually pulled me aside one day and said, “Why are you giving up on singing, Tim? You could have a real future in that!” Sure, man, sure. I just checked on Facebook—that guy is now a Choir Director at a middle school in the Dallas area. I literally just found that out now as I’m writing this. The irony…does…not…escape. Shoot for the stars there, buddy. Not knocking teaching by any means; I just find it scary when schools train people with a skill-set that can only get them jobs teaching the skills they just learned. It’s a snake eating its own tail—when you think about how many people graduate art-school with their only prospects being teaching art-school, you start to see the pyramid-scheme that is a liberal arts education. There only so many positions out there, guys.

With that said—it comes as no surprise when I say I didn’t go to an arts college or get a 4-year degree. I spent three years dicking around at Colin County Community College, finished their arts program there and just hung around taking life drawing and watercolor classes. I took watercolor because Alex Ross. I really did like the art classes, because they gave me time to paint and draw, but I don’t think the staff knew what to do with me. I wanted to paint Star Wars book-covers, and they wanted to do abstract expressionism. Once I realized that I really couldn’t learn what I wanted to do from the teachers there, I just kind of gave up. I was smart enough to know I didn’t want student loan debt, but not smart enough to know where to go next. So, I went to Austin in ’99—four years after High School—and that’s where I am now.

Before we move on, I want to say my two best friends in high school and through community college were these identical twins—James and Jason Adcox—they were just amazing realist acrylic painters, and comic-book guys, as well. Being friends with those guys really kept me working at my craft through high school. I wanted to be better because they were so much better than me. It’s important to not be the smartest guy in the room, the best artist you know—all that stuff. You can stop growing at that point.

It seems that so many artistic dreams get abandoned simply due to having no outside support or nurturing. Every aspiring artist should be lucky enough to have parental support and a pair of painterly identical twins to inspire them.

The point you make about art academia’s self-devouring nature is interesting (and a bit sad), because that’s the sort of complaint that used to be primarily reserved for degrees in things like Poetry, Philosophy, and Gaelic Literature, yet there is so much demand for art and illustration in the world—in practically every industry there is. So, if I took out, say, this gun right here, and put it to your head—like so—and forced you to become an art professor RIGHT NOW, what would you change in the world of art-school academia to make it a more valid degree, and less of a tail-eating snake? I’m giving you total dictatorial control here, so long as you don’t get hair gel on my gun barrel.

I’m surprised and saddened that this came to firearms so quickly. Normally that comes later in most my interviews. Well, it had to happen sooner or later.

The one thing they can’t teach—which is why most of these people become teachers—is how to get a job as an artist. You need to have real social networking skills; you need to know how to romance a client (in a strictly platonic way…obviously); you need to know how to manage your finances, how to negotiate a price, how to stick up for yourself when it comes to contract negotiations; you need to know how to walk away from a bad deal. These schools can fill your head up with theory and self-doubt and crippling self-examination. And don’t even get me started on artist statements. I’d just chuck that shit out the window Day One. Sure, you can self-analyze and tear apart what your inner machinery is to find out why you make art—but it can be like pulling a grandfather clock apart: you’ll never get all the gears back in the right place. It doesn’t matter why you make art; it just matters that you do make art.

Here’s my main reason why I’m so down on going to a college for art: debt. There is nothing you can learn in school that you can’t learn yourself on your own now. Tutorials on YouTube, a few good books, a couple of like-minded friends, and the will to draw is all it takes. But if you’re swimming in debt from school, you’re going to have to get a day-job to service that debt. With that debt, you’re going to have to make decisions you wouldn’t otherwise because of it. All this is time spent not drawing. Because let me tell you: if you go to sit down with, say, an editor at Marvel Comics and get a portfolio review, all they’re going to give a shit about is if you can draw Wolverine real good. If it comes down to you and a guy who got a degree, the degree is irrelevant to who actually gets the job. And if you spent time practicing your craft while the other guy had to worry about passing math and science and history classes—while also working a job to pay off his student loans—you are going to be the guy with the skill. End of story. Now, those classes are great and all, and will make you a well-rounded human being. But that’s not what you want to do—you don’t want to be a well-rounded human being—you want to fucking draw Batman for a living, so you’re already a weirdo; why try to hide that? I’m using comic books as an example, but this applies to any art field—no one gives a shit what your degree is in, they just want to know if you can deliver. “But I need school to help me produce—I need someone giving me assignments or I’d just never get work done!” Well awesome, perhaps you should have majored in XBOX or whatever your passion is because it certainly isn’t drawing stuff. If you’re not making stuff on your own and need someone behind you pushing in an academic setting…that’s cute, and all—just make sure you take my order down correctly, I said I wanted a Diet Coke. Yes, I’ll pull ahead to the next window.

Wow, an art professor AND a life coach! You really deliver the value when wantonly threatened with violence! But it’s damned solid advice—when it comes to a career in art, it’s far less about credentials than it is about ability and drive, especially in the comics medium (or any illustration-for-publication arena), where the ability to meet a deadline is so much more vital than accumulating a haughty list of past accomplishments.

So, after realizing that the academic path wasn’t the path for you, you set sail for the much-more-culturally-enriched land of Austin. Did you have a “lost and wayward” period there before you started getting the kind of jobs that could pay your bills, or did you hit the ground running and start getting yourself work fairly quickly? I guess I’m looking for what led you to the job or time that you feel represents your “breakout moment”—when you genuinely started feeling like a “professional illustrator” rather than a “struggling artist”.

Oh, man…so this is kind of a long and meandering story.

Back in Plano I had worked off-and-on in a baseball card and comic book shop, I managed a Kay-Bee Toys, and managed at a Suncoast Video. Kind of just nerd-adjacent jobs. When I moved to Austin, I just of sat on my ass for a few months and blew through my savings. I was 22 and was living away from home for the first time. My parents had given me precious little to rebel against, so I never had the urge to rush out the door as soon as I could. However, a bad break-up finally got me to leave town. After running dangerously low on funds, I got a job at a Hollywood Video in probably the worst part of town that had a video store at the time, and it was everything you’d expect it to be. Massive customer and employee theft—no one gave a shit at any point—as long as some money made it into the safe and no one was shot that day, it was a good day. We did rent a surprising amount of Leprechaun and Chucky movies, though. The lesson? Poor people like killer midgets. They tried to make me a manager there and I took one look around and just quit that day. No way in hell was I going to be responsible for that mess.

I went down to Asel Art supply by the UT campus and got a job there, and I really started experimenting more with different mediums, and began doing more canvas paintings. Talking to all the artists coming in the store, combined with a healthy employee discount helped me get a handle on the art scene here. After doing that for a while I started showing art in coffee houses and restaurants here in town, and surprisingly, the work started selling. From there I began showing in some local galleries like the late, great Gallery Lombardi. It was never enough to pay bills, but it was certainly nice. I was dating a girl who was also an artist, Jen Frost Smith, and it was a pretty cool set-up for a while. I eventually moved from there to waiting tables, and then to working at the comic book store on campus, Funny Papers. In August of 2001, I started a diary ‘zine called Amazing Adult Fantasy, where I’d do a daily 3-panel strip about what happened that day, and I would print them monthly and distribute them around town for free. That was inspired by both my friend Jeff Lewis’ (sorry…Rough Trade Recording artist Jeffery Lewis!) diary comics, and local legend Ben Snakepit’s diary ‘zine, Snakepit. The ‘zine was excellent PR and became a promotional tool for my art shows and raised general awareness. This was all before social media was really a “thing” yet, and I daresay it was more effective on a local level than those outlets can be now. Amazing Adult Fantasy ran for two years and 25 issues.

I was painting and drawing this whole time—while at Asel I begun work on my 3-issue comic, Sally Suckerpunch, which was a lot of fun—all my comics work at this time was done totally without the benefit of computers, too. (I really could have used a digital pre-press and Photoshop classes, come to think of it…)

About mid-2002, Funny Papers was in danger of closing down, and the owner sold it to a high-roller customer with the caveat that I would run the place. Within a few months, we had cleaned the joint up, and doubled monthly sales. Then he acquired another shop, called Thor’s Hammer—mostly a table-top gaming/RPG store—and a few months later he purchased another “distressed property” called First Federal Comics. And I worked my magic by cleaning up and standardizing the shops—just applying the basic tenets of retail that I had learned from my previous management experience. And sales at all the stores shot up double or more each time. See, most comic shops are started by comic book fans who think their love of the medium will carry them through—and while you must be a fan to jump in, if you think that at any point it’s going to be easy or fun all the time, or you can somehow subvert the laws of retail, you are in for a rude awakening. It was eye-opening and very educational for me, learning every aspect of a retail business from all angles. But the problem was…the guy who owned these shops—that high-roller customer who purchased the businesses that I ran for him—was totally insane. As time went on, I spent more and more of my time just trying to keep him away from the shops, away from the employees, and away from the customers. He didn’t actually read comics anymore, or even know what the customers were buying. He was just a guy with a decent amount of cash, and he thought—like a lot of people with money think—that they have money because they are smart. That’s rarely the case. I had pretty much stopped drawing at this point—no longer painting or doing my diary comic—and I was miserable at my job; I started having panic attacks from the stress. The owner was calling me “faggot” more than I ever was called in middle school—he was blowing all the cash on things like a Porsche instead of product, and generally being a huge bastard. Oddly, in all seriousness, he gave me a sword one day, saying it was an ancient sword that I should hold on to and pass down through my family, and he had the matching sword and would do the same, so our families would always be linked. It took me about 30 minutes to figure out it was a HIGHLANDER prop replica sword. (I later found out he did the same thing to the next guy he hired to replace me…) So one day I just walked out, left my key on the table and jetted. Within three months, one of the stores closed down, one caught on fire and then closed down, and the other changed hands a few times before being padlocked shut for back-rent payments. Again, he had money…but was not smart. Somewhere in there I started dating the woman who is now my wife—Angie Genesi. If it wasn’t for her, I would’ve probably stuck around at that job, but something in her made me more confident and daring, so it wasn’t as scary as it should have been.

From there I called up a friend—Henri Mazza—who was programming shows at the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema here in Austin, and I just took an entry level position as a food-runner/ticket-taker there, until they could find a management position for me. I was a cook and a waiter for a while, which was a lot of fun, actually. Being a line cook was intense. That eventually led me to being hired to run the floundering Mondotees.com, which was a bootleg t-shirt shop and website that the Alamo Drafthouse ran out of their hallway in their old downtown location. They had blown through something like three general managers in about six months. It was a concept they had thrown together as an afterthought, and never had anyone that could take the reins and see it bloom. Which was more their fault than anything—I was just thrown in there with the instructions of, “Make it work!” and just left to my own devices, mostly. At the hours I had to put in, and the pay I was receiving, any sane person would have just walked away—no, should have walked away. I ran that place for four years and took it from making barely $70K a year to over $500K by the time I left. When I came on, Mondo had a dog-eared stack of posters in the back closet from past cinema events that no one really seemed to know what to do with; I thought they were pretty cool and wanted to do more. Working with artist Rob Jones (who was an outside advisory kind-of-guy at this point), I turned it into a juggernaut of a print series. Rob had all the artist contacts and the print industry experience, and I had the list of upcoming events, ran the site, and cultivated the press contacts—and it worked beautifully.

But…I had done a few posters for the print series myself when we needed someone on short notice, and they did really well. Working 60 hours or so a week for $35K a year can start to grind on you, so I asked if I could get paid for the prints I was doing. Well…I was told “no”, that I was on salary and I couldn’t be paid anything extra. So I pretty much shut down at that point. I was on salary as a retail manager, but I was doing about 70% of the t-shirt design, organizing releases, hosting a small amount of events, designing retail spaces—pretty much everything an owner of a small business would do—but I had no ownership, and my pay wasn’t up to where it needed to be. So me and a friend I had at the time—Justin Ishmael, who also was working at the Alamo, and also was very tired of the treatment he was receiving—started laying ground work to start our own business, which eventually became NakatomiInc.com.

We launched the site in January of ‘09, and shortly after that were called into a meeting at the Alamo where they gave us an ultimatum of either giving them the company we had just launched, or we’d have to go. I left (as that was the plan—to not work there anymore), but I guess they pulled a big loyalty play on Justin, and he stayed. They gave him my old job of running Mondo, where he still is now, and I went off on my own.

It was never really my plan to become one of the main artists on Nakatomi…I mean, we had working relationships with some of the best artists out there at launch, but after a couple prints I did sold out immediately and went viral—mainly the Change Into a Truck design—it became evident that people liked what I was doing and it was a great way to pay the bills. Shortly after that, my wife and I decided to get married, and somewhere around March we found out we were pregnant for the first time with our son, Rocco. If I had known I was going to have a kid that year I never would have left my job—which, with the way things are going now, would have been a huge mistake. Nakatomi has blown up much larger than my expectations could ever have been, and my own art career is doing well. All that I would have missed out on if I stayed at Mondo.

So…that’s my not-so-secret origin story. Really meandering, but I think it’s important to see what decisions and random events led me to where I am now. Rolling with the punches, and all that.

But—to answer the main thrust of your question—when did I know I had “made it” as an Illustrator? I’ll let you know when that happens. I still feel like I’m constantly hustling. I think when my first solo SpokeArt show in 2012 sold out within a few days I realized I had reached a new level in my career. The money was really nice, and we paid off my house that year. I guess that more than anything said I had “made it”. No longer having a mortgage over my head means I can slow down a bit and focus on more long-term goals. That goes back to my earlier statement about debt—financial debt is your enemy if you want to be an artist. I launched my business without borrowing money, haven’t used a credit card in about four years or more, and have no car payments. And I got there with a series of smallish advances in my career, a few bona fide “hits”, but really it’s just a constant grind.

Would you say it was your time and experiences working at Alamo Drafthouse and cultivating Mondotees that moved you more toward the medium of movie posters and fine art prints, rather than becoming a full-on comic book artist, or was poster/fine art more of the direction in which you ultimately wanted your career to go?

Oh, absolutely. Like I said, I had been painting and doing comics for a while in Austin, but neither one of those mediums was really paying off in a way that I could support myself doing it. Making a living at comics seemed like a pipe dream from where I was at—I wasn’t good enough to do it at a “Marvel/DC” level—and I didn’t have the knowledge to produce my own at a professional level and deliver it to market through the distribution channels that were available at the time. Once I moved in to Mondo and saw the potential and reach of silkscreen prints, I was definitely hooked. The successes of my early prints while I was there really lit a fire under my ass and got the gears turning. I learned every step of the process while I was there, from commissioning artists, designing prints, overseeing production, art direction, marketing, selling, fulfillment, the aftermarket—everything you needed to make the art and sell it. Having Rob Jones on speed-dial 24/7 was very influential; his knowledge base and guidance was crucial in my development as a silkscreen artist. I guess in many ways, by putting one guy in charge of all that at Mondo, they gave me all the tools I needed to just leave and do it myself. And for that, I’m very grateful, but I’m sure they were kicking themselves over that in the weeks after I left. (They do seem to do okay now, though, so no loss on either end.) I had minimal experience with selling things online before, but once I got my hands on the back end of Mondo and understood all the moving parts, I realized not only was it super-easy to do, but the only thing that mattered was content—and I knew how the content got made. My friend from the Dallas area, Nathan Beach, had done a lot of web design for me and other artists and musician friends (like my brother, Daniel Francis Doyle! PLUG!), so I tapped him to do the heavy lifting on the functionality of the site. God bless him—he did it all on faith with promise of pay on the back-end, and I’m eternally grateful for it. It paid off for both of us quite well. He still works with us today.

Oddly, as I’ve become more skilled and become friends with more and more comics professionals (and as some of my old friends have become comics professionals), I’ve received more and more offers for work—and the sad thing is that the shine is off that dream for me. I have a couple good friend who currently do work for Marvel and DC, and those guys…are…very…tired. It’s a 12-plus-hour-a-day job with no time off to stay on that monthly grind. And the pay isn’t what it was 20 years ago, so there’s even less of a reason to do it now. I love comics, but at this point in my life, I think I’d rather be reading them. If I could afford to take the time off from what I’m doing now to make comics of my own, I could see myself doing it again, but right now everything is running really smoothly, so I’m a little afraid to step off this merry-go-round to do something more indulgent like comics.

I guess as far as the direction I wanted my career to go in—I never really gave it much more thought than this: can I get paid to draw what I want to draw? For right now, that answer is yes—so…mission accomplished?

Funny how quickly the glamour can dissipate when you get the insider’s perspective on something, isn’t it? Comics seem like a dream job to so many until they discover the labor-to-pay ratio in the industry. But still, t’would certainly be nice to attain the stability and freedom to do a comic for the sheer pleasure/inspiration of it, and not out of financial necessity…it sure would make all the labor required feel a lot less like “work”.

I want to ask you a bit more about your movie-related work. You’ve earned quite a bit of popularity from creating original posters for some pretty iconic films’ revival screenings. When it comes to taking work for movie posters, are you picky? Have you ever turned down an offer because you disliked the film, or maybe accepted a job you normally wouldn’t have if you weren’t a fan of the film?

Well, any freelance artist worth their salt can find an “in” to make just about any job interesting enough to do. There’s a weird thing in the print-collecting community where collectors think that every print an artist does is done out of “love” for the band or film. But the truth is a lot of artists do gig posters or movie prints for stuff they pretty much couldn’t care less about. I know a ton of artists who’ve done work for Phish, and almost to the man, they say they couldn’t give a crap about Phish—or downright hate the band and their fans, but the prints sell like gangbusters, so they take the pay-day and move on. The nice thing about gig posters is that usually the band or management just wants a cool drawing with the band’s name on it somewhere—so you can have an awful lot of creative freedom that way, and still get paid. I’ve done four prints for country musician Eric Church, and I’ve yet to make it through more than a couple songs. But…I did some research to make sure he wasn’t an obvious racist or anything and found he’s pretty progressive as far as I could find. And, most importantly, the design brief was great. It was pretty much (and I’m severely paraphrasing here), “Draw old rusty homeland middle-America stuff.” That, more than anything is what hooked me. And, I think those four prints hang together in a consistent design sense, and I’m pretty proud of ‘em, even if I have nothing in common with your average Eric Church fan.

Movie prints are a little more challenging, as the key visual moments and iconography are already built in to the property, so you have to find a way to remix them into your own design sense that is pleasing to you and the client. I’ve been pretty lucky in that just about every straight-up movie poster I’ve done—I was a fan in some way of the movie already. There are a couple exceptions—FANBOYS was difficult as the movie is just…so…blah. But, I was able to find a way in, because it’s essentially about Star Wars fans vs. Star Trek fans, and so that’s what I drew. I actually was contacted by the studio, as they wanted copies for their offices, and the guy who wrote the script is a local writer, and he was super-into it. So this film I really couldn’t stand to watch again still spawned a final print that pleased me, the theater who commissioned it, and even the production team. (BTW, the credited writer of the film would agree with my assessment of the film as it was shot.)

As my career has progressed, though, I have been able to be more picky, and concentrate on just the stuff I want to draw, so that’s a nice bit of freedom, there.

Now that Nakatomi, Inc. is up, running and proven successful, are there many things you would have done differently with the benefit of hindsight? Did you have preconceived notions going in that proved to be totally wrong, or did you pretty much work out the majority of your birth-of-an-art-dealer growing pains when you took over Mondo?

Well…not really. I mean, there’s probably a few prints I might not have done, or done differently based on sales in hind-sight…or a couple people that I would have cut out at the very onset, instead of learning the hard way that some people were just unreliable. But really, it’s been such a great ride that I don’t think I’d change much, if anything. Although, I guess I would have started Nakatomi sooner. That would have been better.

I will say that everything we thought was going to be the “big hit” products at launch ended up being the wrong ideas entirely. Not that we lost money on them or anything, but the learning curve was steep and came at us quickly. I really thought t-shirts were going to be a bigger deal than they ended up being.

I try to learn from every experience—my next decision is based solidly on the results of my previous one. What some people might call a failure, I just see as a learning experience. I try to question the norms of every business model, find gaps to exploit, new markets to move product to…and I’m afraid that if I didn’t have so many wrong guesses in the past to learn from, that I’d not be making the right ones now. And by “afraid”, I mean only if I’m suddenly in possession of a time machine and could correct those mistakes. Not too likely. This week.

Yeah, but…if you acquired a time machine, who knows WHEN this week would be…OR WILL IT???

(Pauses for dramatic effect)

So anyway, if I were to force you back into the role of Art Professor/Advisor again (sorry I can’t threaten you at the moment—using my gun barrel to stir coffee), what advice would you offer artists and entrepreneurs who aspire to get into the world of Fine Art Production that they never would’ve thought of in a million years? (If you feel I’m unfairly asking you to help out your future competition, feel free to unleash piles of bullshit advice that will steer them in all the wrong directions…just twirl your mustache menacingly whilst doing so, please.)

There’s a mistake I see new galleries and websites and artists make time and time again—they see what other successful businesses do, and try to emulate that exactly. They make the same kind of products, use the same group of artists, and market to the exact same narrow customer base of print collectors. That will work…for a while. Until it doesn’t. And if you’ve built your entire business on appealing to this small group, then the whole game will be up. These businesses aren’t diversifying enough. I work really hard to get my work in front of new customers, while not ignoring the old ones. It’s important to keep branching out. There’s a bit of elitism in the print collecting community where they want to believe they’re collecting “real art” and other people are buying mass-produced crap. Well, when Mondo sells millions of dollars of posters a year, what exactly is a mass market again? The elitism is dumb and insular and will lead to a collapse. The smart people in the industry see it, and are making plans for it. People criticize the “house-mom” crowd of art-buyers, but I’d much, much rather sell prints to people (yes, even house-moms) who just want cool, cheap art on their walls than to a diminishing group of extreme hobbyists who think they’re going to retire on their poster collection. If you believe that, I have a collection of Beanie Babies to sell you at a screaming deal.

On one hand, I shouldn’t be giving this advice, because, yeah, competitors could benefit from it. But the way I see it, a rising tide raises all ships—the healthier this industry gets, the more it will benefit everyone involved. And I think I’m a decent enough artist to keep my head above water, no matter how deep and wide this pool gets. (To completely murder a metaphor, here.)

Also, listen to your customers, but don’t let them dictate your business. If I listened to what the noisiest people online wanted, I’d be broke-ass poor—but that small group would be really happy. But the wide group of customers I sell to who aren’t active in the online poster community more than pick up the slack from any of those from the smaller group I alienate from time to time.

Finally, don’t be a victim to middle men. There are some middle men who can do great things for you—Ken Harman at SpokeArt has worked his ass off to raise my profile, and it’s been very beneficial to both of us. Other middle-men are just sponges. And when I say “middle men” I mean anyone that stands to profit by the interaction between you and the customer. Make them work for it. Too many artists just sit on their hands and wait for permission to come down from on high to do something. And that’s where the middle-men can benefit and make a buck off your labors. You don’t need them—just build your own thing, make it well, and the customers will find you. Contact a band or a movie theater directly to do a poster. Learn to print. Build your own site. You can no longer be “just an artist”—you have to be your own promotions machine, your own agent, and a businessman. It’s hard work, but if you want the small measure of freedom I’ve carved out for myself, then get the fuck to work.

And finally-finally, price your work properly. Don’t be afraid to shoot for the stars. If someone comes to you with a gig and a budget, that’s great. But if they ask you what your rate is, ask for what it would take you to feel happy to do the job. And then throw some extra on top of that—because you’re not going to be happy for the entire job.

I could go on and on, but really—so much of this you have to learn yourself, honestly…

One of the things you do that sets you apart from many other purveyors of Fine Art involves the occasional release of multiple editions of certain images—which REALLY seems to upset some of your customers and contemporaries. What do you have to say for yourself about that, Mister?

Well…this is the one thing that’s caused me the most grief while also raising my profile and made me the most money. So mostly a win, there. It’s something I feel very strongly about. That’s not to say that someone might come at me with a very reasonable, logical opposing view one day—and I might change my mind then. But I’ve been defending myself against poorly-thought-out opposing views for so long now, that I may have become entrenched in my position.

Here’s the skinny: I sell art. Usually, I print an edition of a piece in a quantity of as many I think I’m going to sell in about six months or so. That’s the first edition, signed and numbered in a fixed quantity. (Like this: #45/300 total made.) Sometimes I print too many; sometimes I print too little, and a print sells out immediately. Now, if we were talking about books, or albums, or DVDs or hamburgers or any other form of consumable entertainment items, you would just make more. I don’t want to make collectibles. I want to make and sell art. But, there’s a financial-collectible aspect that some people want to put onto these items. And yeah, that aspect of the industry exists. A segment of the buying public wants to buy something and turn around and sell it immediately for profit. I have no loyalty to those people. They are an aberration of the marketplace. I have no problem with them buying my art and doing this—once they buy it, they can do whatever they want with it. Another portion wants to buy a limited item and be one of only a small handful of people to own something—this is how they feel special, and part of their identity is wrapped up in what they own. And, as a former action figure collector, I recognize that’s a thing. But I also realize that defining who you are by what you buy—rather than what you do—is a problem with society. These groups of buyers want me to play by the rules that they established for their hobby—they want me to make one edition, and when it’s gone, it’s gone. They get to profit from their purchase or be a member of an exclusive club. And they scream to high heaven when I do a new edition of a print. My new editions are always differentiated in one way or another—by color, size, a Roman numeral by the edition size, and lately I’ve been just clearly putting a “2nd Edition” near the margin of the art to keep it simple.

But consider this: how many printings of A Christmas Carol are there? And yet…if you have a first edition, you’re sitting on something both valuable and exclusive. No one is walking into Barnes & Noble (do they still exist?) and throwing a fit that there’s shelves full of subsequent editions of a book. No one is setting fire to their first pressings of Beatles albums because I can now buy ‘em on CD. And yet, some of these “investment collectors” think my art is now devalued because more people can get it. It’s just ridiculous.

Put your self in my shoes—I do a drawing, and print it. It sells out, and I get a ton of emails from people who now want copies. I can say, “Nope,” and I make less money, and those people are sad. Or…I can say yes—make more money and make people happy—but run the risk of alienating a small portion of the potential customer base. It’s a no-brainer for me. In any other business, if you are leaving money on the table, you have done something wrong. The customers you lose by not having something in stock that they want to buy may never come back.

Some of those critics will read what I’ve written there and say, “See, I told you he was greedy!” And to that I say: I run a business. I pay my bills by doing that. I do not have a day-job to fall back on. I feed my children, pay my employees, and pay for health insurance for them and my family from that. You go into your workplace and argue that they should deliver less services, less products, pay their employees less, and make less money because…something something. See what happens then.

There’s a website out there that tracks new print releases and their after-market value through a database of eBay sales. And it’s an amazing tool. They also have a fairly active forum there. I was attacked there for doing what I do, and I used the site’s own database to prove that nothing I was doing was lowering the “value” of a particular print—the sales were still trending up. Once I saw that my logic wasn’t going to be listened to, I realized that the people doing the loudest complaining were just crazy people who wanted to yell at an artist online without fear of repercussion—hiding behind a user-name—and that there was no reason for me to engage in an online debate about it ever again. The people that buy my stuff buy it because they like it, and those that don’t buy it aren’t going to be my customer anyway, so there’s no reason for me to keep them “on my side”.

One thing I’m able to do with these further editions is really grow the hobby at large. I get emails time and time again from people who say things like, “My first print was a 3rd edition of Change Into a Truck, and now I’m a print junkie!” Or, “My boyfriend bought me the 4th Edition of White Dragon, and now I’ve purchased art from a bunch of other artists! I love it!” Which is just amazing. Would the world (or me) be served any better by getting emails like, “I saw a cool jpeg of a print on line, and I couldn’t get it; I guess prints are dumb.” Which are the kinds of emails and blog comments I see on other art businesses’ sites. For every investment collector I might alienate by doing a 3rd edition of my squid print—that’s 300 sold copies of my squid print that went out to people who might turn into print collectors one day, and really grow the hobby. That growth is key to the health of the industry.

I’ve seen first-hand what happens to niche hobbies that cater only to a diminishing collector customer base. Comics, baseball cards, etc. These hobbies move into selling collectibles and bank on the idea of “aftermarket value” to drive sales, and that creates hype—and you can make money at it for a while…sometimes a lot of money—but the thing about bubbles…is bubbles—burst. Baseball cards are never coming back. Comic Books are still a fraction of the sales they had before they were sold as collectibles, and a smaller fraction of what they were selling at their height of “collectability”. The problem is that these businesses lost track of what they were selling—comics are stories and art—baseball cards are cardboard pictures of ‘roided up millionaires. At no point should these items have been sold as “collectible”. It’s going to happen at the consumer level regardless, but to foster that attitude is some baaad mojo. It never lasts.

I’m in this for the long haul—I’m going to be doing this for decades to come—and I want a healthy industry to be here to support me. One full of a wide, diverse group of customers. And you’re not going to get there by alienating the general public and appealing to a diminishing collector base of people that—let’s be honest—are only are into it for the wrong reasons.

What really kills me (and forgive the ramble, but this is important) is when I see artists pushing back on this. All artists talk to each other in this scene. Whenever the subject comes up, I hear from a few that they “wish” they could do what I do, but they’re afraid of what their customers would say. To which I always say: If you’re afraid of your customers, then it’s time to get new ones. These giants of the industry—these amazing talents who struck out on their own to work for themselves—are afraid of a couple loud-mouths online. And that’s sad. Even more surprising is when lower-profile artists feel the same way. These are people who get a hit every once in a while, and maybe have day-jobs, but certainly aren’t living large, and they’re afraid to break the rules of a collector base that isn’t even buying their product to begin with. They’re living hand-to-mouth in the hopes of getting non-existent customers—while real actual customers are in line with cash in hand—but they have no “hot” product to sell. It’s madness. Now…I’m a good artist. Not a great artist (at least in my estimation…gotta keep that ego in check), but I’m doing “better” financially than the majority of my contemporaries. And that’s because of this. I live in a reasonable house in a lower-income neighborhood; my cars are all over six years old. But…they’re paid for; I have health insurance, no debt (even the house is paid for) and a Self-Employed-Pension I pay into every year. That kind of security is priceless for a freelancer. I didn’t get there by catering to the loudest, jerkiest segment of the online community. I didn’t do this by following rules that people I never met decided to apply to this scene. You guys can do this, too.

There’s a line of thinking out there that artists shouldn’t be aware of money like this. Shouldn’t think of business models. It’s the myth of the “starving artist”. It’s an entrenched idea that must be smashed. Trade out the word “artist” for any other profession and you’ll see how crazy this is. “Starving plumber”. “Starving IT professional”. “Starving Realtor”. In any other profession, making more money and being aware of how to maximize sales is considered a good thing. But as an artist, there’s the idea that is supposed to be a bad thing. Smash that idea, burn the pieces and dump the ash into the sea, because that’s harmful to everyone involved.

I have a large group of amazing, loyal customers, several galleries I deal with, about a dozen consignment shops who carry my work, and until my sales go down I’m going to assume that I’m proceeding properly. The business keeps going up every year so…yeah.

I couldn’t agree with you more on the whole “starving artist” sentiment. It’s a fairy-tale mystique that belies the whole concept of an artist who works hard and achieves success at their profession, as if success is something to be avoided in order to remain noble. What a crock.

I’d like to ask you a bit about your process as an artist. This may be a bit too in-depth-geeky for some, but it is something I always enjoy hearing artists talk about, so any disinterested readers can just skip this part. Once you have an idea for an art piece that you want to create, can you walk me through your usual process, from conception to finished piece? I know it depends on the project, but just in general. And be as meticulous in detail as you like, right down to pencil/brush/pen types and ink brands, and any other tools or weapons you might wish to reveal.

My process varies from print to print, but the majority of them go like this: Once I get a gig, I watch the movie or listen to the band, and just see what pops into my head. I usually know what I’m going to do before either is through. If it’s a gig that needs photo-references, then I take screen grabs using VLC on my PC, and spend a lot of time on Google Image search. Also, if it strikes my fancy, I’ll read up on a band or movie on Wikipedia or whatever, just to see if there’s some nugget I could latch on to. So I sketch something out on whatever scrap I have laying around, then I do a full drawing on Bristol Board from there. If it’s a likeness of an actor, I’ll usually lightbox a face on my lightboard. I use pencil to lay it all in, and then I ink with a variety of pens or brushes, depending on the look I’m going for. For pens, I use PITT Brush-pens, or their liner-pens if it’s more detailed. I actually just ordered a Gross of these Pentel ses15n brush-tip pens—they’re a little more springy and tighter than the brush pens, but you don’t get the broad lines you can with the PITT pens. It’s a mixed bag, really. If I’m using an actual brush, I have a couple sable-hair watercolor brushes I really like, and have had for years now. Probably a decade at this point. For ink, I really like the deepness of the FW acrylic black ink.

There are a couple art supplies I have that belonged to my father, like a broken old ruler, an ellipse template—stuff like that. They’re nothing special, but the history of them is what makes them important. And they work really, really well. Using them is comforting. I’ve had those for about 20 years or more now. Crazy.

Once I have a finished black and white drawing, I’ll scan that in chunks on my 11×17 Mustek scanner (real cheap on eBay!) and composite the parts together in Photoshop, and start the coloring process. I work in layers, with each color on its own layer, so by the time I’m done with that, the separations are ready to go already. Some artists will spend weeks doing separations on a piece, but mine are already done as soon as the coloring is laid in.

Then I send the layers out for flim, get the film back in the shop, and I hand those to my employees—and then magic happens. Step 3 is profit. No idea what step 2 is.

Suuuuure…just conveniently skip over your blood-sacrifice-related step in the process. You’re not fooling anyone, you know. But we’ll let that slide for now to avoid legal repercussions.

So, for pieces like your BLADE RUNNER character prints, were those client commissions, or more “because Tim just loves BLADE RUNNER”-inspired pieces? What is the approximate ratio of for-print work you produce from client commissions versus work you produce because you’re just feeling inspired and think it will sell? And in the instance of the latter, how do you generally gauge your confidence/predictions on the piece’s sales potential?

Well…I love the hell out of that movie. And the portrait/character series was something that I did to give away to customers as freebies. None were ever actually sold. The nice thing about having a print shop is I can afford to do stuff like that. I’m doing the same for Doctor Who right now, actually. One character…so many faces!

Honestly, it’s been a while since something has come along completely on its own from my head—I’ve been so booked up with client and gallery work, I haven’t done a straight-up “art print” that was completely of my own instigation. Even my last two The Sea Also Rises prints I did were for either a client or a gallery show. I was just able to bend the theme to something I wanted to draw, ultimately. I’m participating in a show this December in Chicago that is grouped under the loose theme of “evolution”, which is great as you can pretty much do anything you want with that. Those pieces will be more “me” than anything I’ve done this year.

As far as making things because I “think they will sell”—sometimes I purposefully do shit that I don’t think anyone is going to buy, and see if it can find an audience. And I’ve yet to be let down. Not that I’m making things that I think are bad—I’m just shooting for the narrow band of, “This is exactly what I want to draw—who knows if anyone wants this?” Audience of one—or, I should say—audience of me and my wife. I like drawing stuff I think she’d like to see as well. My Goldie’s Big Break print was something just so incredibly personal for me (which is a weird thing to say if you’ve seen it) that I was surprised anyone wanted it. And while it wasn’t an instant sell out, it’s sold steadily and I’m down to like 3 copies now. So that weird little print found its audience, and I couldn’t be happier.

Regarding confidence in how something will do…I always expect failure. I don’t know if that’s a self-defense mechanism or not, but I try not to set myself up for disappointment. And, if something does well, I’m over the moon. But—ask my wife—I’m usually a wreck before a release. Once I hit “sell” on a product, I usually run right to the gym or something to distract me for a while. The way I run my edition sizes is I try to print what I think I will sell in a few months. And I have so many sales channels now; I can spread around the “duds” to a bunch of outlets to where they’ll eventually find an audience.

Through Nakatomi, you’ve now worked with some pretty prestigious and renowned talents—most recently, Bernie Wrightson and Geoff Darrow. Are there any “dream client” artists you’d like to land for Nakatomi? (Or maybe some that you’ve already lined up that you’d like to shamelessly name-drop?)

You know, the list of people I’ve been fortunate to work with though Nakatomi—either through publishing/selling their work on the site, or doing print jobs for them—is just amazing. Tyler Stout, Olly Moss, Jermaine Rogers, Todd Slater, Horkey, and many others on just the poster artist side of things. On the comics side, I’ve got Paul Pope, Shaky Kane, Wrightson, Darrow (more to come!) and on and on. It’s an amazing line-up if I stop to think about it. I literally have more artists lining up to work with me than I can fit in the schedule, while also at the same time doing my own work. It’s a great problem to have, that’s for sure. I think it’s because I offer one of the better deals out there for them now, and I try to make it as easy as possible to bring their work to market, while also exposing them to an audience they might not otherwise have. (Specifically the comic book guys on that one.)

But as far as artists I’d like to work with in the future…man, I’m just mainly excited to do more work with the ones I have. Most of the people I work with today are actual friends—Russ Moore, Jon Smith, Jacob Borshard—and yes, it’s scary to think that I’m reaching a spot where I’m pretty friendly with guys like Pope and Wrightson. Deep down, we’re all just nerds here who want to make good work, and that’s the binding element. I’m an artist, too, not just some middleman or a fanboy with a job selling art for someone else. And I think they appreciate that element. It’s been quite the ride.

So, what should be causing the world to tremble in fear when it comes to your future world domination plans? What would you like to do in the future in a desired avenue that is, for you, yet un-tapped? (Bear in mind that we already know about your Death Ray, and it only mildly unnerves us.)

Look, that Death-Ray is only harmful for non-believers. As long as you’re faithful to me, you’ve got nothing to worry about.

With that said…I’m not into world domination. I’ve worked for many people in the past who want to crush the competition. And that’s just silly. People feel like they need to be Number One all the time—and it’s not possible, and it’s a fool’s errand. You just do the best you can, and not worry about what the other person is doing. People are going to follow you or they’re not. And sticking your finger in the other guy’s eye isn’t going to change that. Especially when it comes to art—no one is better than the other; just different. I think I have a better business model than most, but I realize I’m not the most detailed or inventive guy out there. But I know I can draw real well; I can network really well; I have a lot of talented friends. I have my fans and I have my haters. It might be the rum I’m drinking now, but I feel pretty Zen about it all.

I just want to draw the fun/dumb/stupid/silly/epic shit I always draw and sell it to people that want to buy it. The only thing that I need is more exposure to people who might enjoy cool affordable art. So show my stuff to your mom. Tell her I said “hi”. She’ll remember me.

My mother? Let me tell you about my mother…

(Removes gun from coffee)

<END OF RECORDING>

You can buy some pretty incredible art by Tim Doyle and other amazing artists at NakatomiInc.com, and you can browse for ages and ages through his galleries at MrDoyle.com.